Common Statistical Misconceptions: A Guide to Key Terms

Clarifying Common Statistical Misconceptions: A Guide to Key Terms, Statistics can be a complex field, and even seasoned data professionals sometimes fall into misunderstandings about fundamental concepts.

Misusing or misinterpreting key terms can lead to confusion, miscommunication, and flawed decision-making. To communicate clearly and interpret data accurately, it’s essential to understand what these terms truly mean.

Common Statistical Misconceptions: A Guide to Key Terms

Here are five commonly misunderstood statistical concepts, what people often get wrong, and their correct definitions.

1. Statistical Significance

What People Often Think:

Many interpret statistical significance as a marker of importance or real-world relevance.

The word “significant” in everyday language suggests something noteworthy or impactful, so it’s natural to assume the same applies in statistics.

The Reality:

Statistical significance simply indicates that, assuming the null hypothesis is true, obtaining the observed result (or a more extreme one) is unlikely.

It’s a measure of confidence in the presence of an effect, not its magnitude or importance.

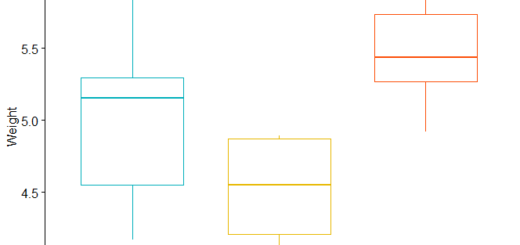

For example, with a very large sample, even the tiniest difference—say, a 0.001-gram increase in cookie weight—can be deemed statistically significant, despite having no practical implications.

The p-value threshold (commonly 0.05) is an arbitrary cutoff and doesn’t denote a definitive boundary between meaningful and meaningless results.

In essence: significance tells you whether an effect is likely to exist, not whether it matters.

2. Confidence Interval

What People Often Think:

Many interpret a 95% confidence interval as meaning there’s a 95% chance that the true population parameter falls within that specific interval.

Statements like “We’re 95% confident the true mean is between 10 and 15” are commonplace.

The Reality:

A 95% confidence interval reflects the long-term performance of the interval estimation procedure.

If you were to repeat your sampling process countless times, approximately 95% of those intervals would contain the true parameter.

Once you’ve calculated a particular interval, the parameter either is within that range or not—probability doesn’t apply to that specific interval.

The “95%” refers to the method’s reliability over many repetitions, not the probability that the parameter is in a given interval.

Think of it as a method that, over time, captures the true value most of the time, rather than a statement about any single interval.

3. Correlation

What People Often Think:

Correlation is frequently mistaken for causation or used to describe any kind of relationship between variables.

For example, “Exercise and happiness are highly correlated, so exercise causes happiness.”

The Reality:

Correlation measures the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two continuous variables. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) ranges from -1 to +1:

- Near +1 indicates a strong positive linear relationship.

- Near -1 indicates a strong negative linear relationship.

- Near 0 suggests little to no linear relationship.

Importantly, correlation does not imply causation.

Two variables can be correlated without one causing the other, and correlation may miss non-linear relationships altogether.

For example, two variables might have a perfect curved relationship yet show zero correlation.

Key takeaway: correlation indicates association, not causality.

4. Normal Distribution

What People Often Think:

Many believe that normal distributions are the most common or “natural” shape of data in nature.

Others think data should be normally distributed or that deviations from normality are problematic.

The Reality:

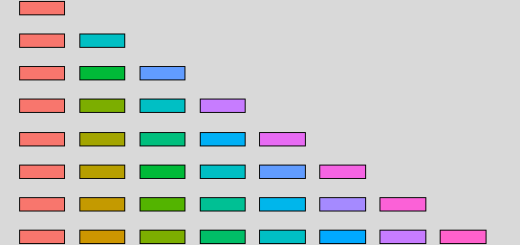

The normal distribution is just one of many probability distributions, characterized by its symmetric, bell-shaped curve.

It appears frequently in statistics mainly due to the Central Limit Theorem: when averaging many independent samples, the distribution of those averages tends toward normality, regardless of the original data’s shape.

However, many real-world datasets—such as income, reaction times, or population sizes—are skewed or follow other distributions.

The importance of the normal distribution lies in sampling distributions and the behavior of means, not as an assumption that raw data must be normal for analysis.

Many statistical tests are robust to deviations from normality, especially with larger sample sizes.

5. Sample Size

What People Often Think:

A common misconception is that sample size only matters if it surpasses a certain threshold, like 30 or 50, or that bigger always means better without considering context.

The Reality:

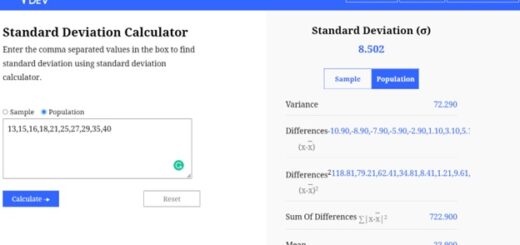

Sample size influences the precision of your estimates and the power of your statistical tests.

Larger samples produce narrower confidence intervals and increase the likelihood of detecting true effects.

However, the relationship isn’t linear. Moving from 10 to 100 observations can dramatically improve accuracy, while increasing from 1,000 to 1,090 might yield minimal gains.

The optimal sample size depends on factors such as the expected effect size, data variability, desired confidence level, and acceptable error rates.

Instead of arbitrary thresholds, researchers should determine appropriate sample sizes through power analysis tailored to their specific study goals and constraints.

In Summary

Understanding these key statistical terms helps prevent misinterpretation of research findings and improves communication with colleagues and the public. Remember:

- Statistical significance is about confidence, not importance.

- Confidence intervals reflect the reliability of the method, not the probability for a specific case.

- Correlation indicates association, not causality.

- Normal distribution is a useful model but not universal.

- Sample size influences the accuracy and power of your study, not just hitting a number.

By grasping these distinctions, you can better interpret data, communicate findings accurately, and avoid common pitfalls in statistical reasoning.